Howard Brenton (1954-1961) by Doug Murgatroyd

Howard Brenton (1954-1961) by Doug Murgatroyd

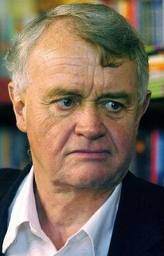

Of all of Chichester High School’s illustrious alumni, Howard is probably the one whom I am most proud of, if only for the fact that throughout our school careers we were in the same class and, at least from my point of view, were good friends throughout our time at the school.

Howard had a great sense of humour and, I seem to remember, a rather quirky, unconventional take on the ways of the world. He was a good artist and, indeed, had aspirations to make a living using that talent. My recollection is that he did indeed go to Brighton Art College for a term or two and decided, for reasons he never explained, that that path in life was not for him. What he did next was remarkable. Without any formal invitation to any college in particular he took himself off to Cambridge and went door knocking at the residences of College Deans to persuade them to take him on as a student and, lo and behold, it worked. Why would it not? After all he had achieved distinctions at Scholarship Level in History and English. Was it his “brass neck”, plus, if my memory serves me right, his Yorkshire genes that did the trick?

Other memories of mine of his time at school were that he was more than a passable cricketer with an amazing “dead bat” and, if he had taken his talent more seriously, would have easily made school teams as a difficult to remove opening bat ; also his love of “serious music”. A small but dedicated group of 6th formers formed a “Music Appreciation Society” in the school listening to 9s 11d Ace of Club Long Players. I usually brought along Rachmaninov or Tchaikovsky, Bob Bearman, Mozart or Bach, and Howard Stravinsky’s “Rite of Spring” or Bartok or Shostakovich. I may be wrong – Memories dim with age!

Some of this next section give some idea of how his writing developed and blossomed during his time at Cambridge and later his association with Bradford University and the Traverse Theatre in Edinburgh, both in corroboration with old school pal Chris Parr, and on to his association with David Hare at the Royal Court. However, we Old Cicestrians would love to surmise that it was his association with Chi Hi that planted the original seed. I am probably wrong but I do recall Howard playing not insubstantial roles in numerous school plays under the guidance of Messrs Wake and Marwood. Perhaps even the proximity of the newly built Festival Theatre had given him inspiration?

Some of this next section give some idea of how his writing developed and blossomed during his time at Cambridge and later his association with Bradford University and the Traverse Theatre in Edinburgh, both in corroboration with old school pal Chris Parr, and on to his association with David Hare at the Royal Court. However, we Old Cicestrians would love to surmise that it was his association with Chi Hi that planted the original seed. I am probably wrong but I do recall Howard playing not insubstantial roles in numerous school plays under the guidance of Messrs Wake and Marwood. Perhaps even the proximity of the newly built Festival Theatre had given him inspiration?

In an interview with Carole Waddis of The Guardian, Howard is asked about his years being brought up in Bognor Regis and those early influences…

Waddis: “That leads us neatly into your beginnings; you were born in Hampshire?

Brenton: I was born in Portsmouth. My parents weren’t living in Portsmouth. They were visiting. I came early and fortunately my aunt was a midwife, so she delivered me.

Waddis: You were brought up in Hampshire?

Brenton: No I was brought up in Sussex, Bognor Regis until I was 17/18.

Waddis: What did that feel like, living in Bognor Regis?

Brenton: It was an idyll. My childhood was an idyll.

You were free; there was the seaside, the beach, you could cycle up into the Downs. It’s a very beautiful part of the world. My parents didn’t have much money. We lived in a council house.

Waddis: Your father was a Methodist preacher?

Brenton: No, he was a policeman until he was 50 and then he resigned. My father was a hopeless policeman. He hated it. He only joined the police because it was a time of unemployment in the Thirties. He never got promoted, he was a constable all his life. He was always religious and he decided to become a Methodist minister when he was 50. So he left the police and put the frock on. We then went madly around the country because Methodist ministers are moved around.

Waddis: Just to go back. You get to Cambridge. What did you read at Cambridge?

Brenton: English.

Waddis: And did you always want to write, where did that come from?

Brenton: I was already writing plays at school. I wrote a play in the sixth form, A Life of Hitler, which has never been done, completely unperformable.

Waddis: Did you always see yourself as a playwright, then?

Brenton: Well, as well as being a religious policeman, my father was also an amateur theatre producer. The local am-dram. I copied him and the way he bound the Samuel French books in brown paper. I wrote my own play and got my friends to do it, based on a comic strip in The Eagle comic paper. So, yes, it’s always been an obsession.

Waddis: Maybe drama and theatre has always been in you because preaching and going into the pulpit is the essence of theatre, isn’t it?

Brenton: No, it’s not, no. The essence of theatre is three people, at least two, probably three people in the pulpit, none of whom agree with each other. Then you’ve got theatre. As in Anne Boleyn. When you’ve got Dean Andrews and Reynolds arguing about should there be altar-rails or not, that’s theatre. But Andrews preaching at you about how there should be altar-rails is not theatre, its demagogy.”

David Hare – Howard’s Co-writer of “the Romans in Britain”

David Hare – Howard’s Co-writer of “the Romans in Britain”

Over the years Howard Brenton’s writing has won him critical praise and awards and created controversy by his take on the life of Christ and his depiction of “unmentionable” sexual acts on stage. Liz Hoggard, writing in “The Observer Profile” sums his career and persona beautifully:

“A controversial voice in British post-war political theatre, Brenton has written or co-written more than 40 plays, as well as journalism, essays, poetry, a novel and TV drama, including 13 episodes of the BBC’s award-winning Spooks. Over the years his writing – visceral, discordant, and often mordantly funny – has been directed at a range of topical targets.

In the best Brechtian tradition, Brenton juxtaposes alternating modes of fantasy and realism. His biggest hit, Pravda, written in 1986 with David Hare, is a brilliant black comedy about a megalomaniac, right-wing newspaper magnate who bears a suspicious resemblance to Rupert Murdoch (Brenton has said they set out to write Richard III set in Fleet Street). The Churchill Play (1974) brutally deconstructs the patriotic myths Britain has spun about itself since the Second World War.

Brenton doesn’t do subtle. He is excessive where it hurts and he intends to hurt, if only to prod the audience into action. As he once observed: ‘I think the theatre’s a real bear-pit. It’s not the place for reasoned discussion. It is the place for really savage insights.’ One famous interview with him in 1975 was headlined ‘Petrol bombs through the proscenium arch’.

But according to Hare, everyone who meets Brenton is dazzled by his niceness. ‘He’s one of the most genuinely genial, pleasant, funny, relaxed people you could ever hope to meet. He’s so different to the image that has built up around the shocked reaction to his work. When Bernard Levin used to write his stupid pieces saying that Howard Brenton and I were out to destroy society itself, if you met Howard, anyone less likely… he doesn’t have a mean bone in his body.’

Brenton has been uncharacteristically silent of late. Had the master provocateur run out of steam? Critics wondered. A major writing force at the National under Sir Peter Hall, who championed both Romans and Pravda, and then Richard Eyre, Brenton fell out of favour during the Trevor Nunn years. ‘I think it’s been a terrible loss to the theatre, his voice, over the past 10 years.’

But theatre’s loss has been TV’s gain. Who would have thought that this most uncompromising playwright would write something as glossy as Spooks? But for all the funky camera angles, Spooks is anti-institution TV. As Andrew Woodhead, producer of series three and four observes: ‘Howard’s knowledge of the world, his experience and knowledge of politics mean his scripts are so real and so prescient. He’ll write something and then it seems to happen. Last year, he did a story about red mercury, which none of us had ever heard of, and then suddenly it was all over the papers. Police were even asking us where we got our facts.’

David Hare, Howard’s co-writer and co-conspirator for a few years and friend says of him,” ‘Like Brecht, there’s this side of him that’s fantastically earthy,’ says Hare. ‘He loves his food, he loves his drink and a good joke. He’s a man who enjoys human pleasures. He’s an intellectual who has a deep suspicion of the high-falutin’. He also has a great sense of humour. Anyone who went through the Romans in Britain experience knows it was truly horrible. Mrs Whitehouse was out to imprison his director. But I’ve never seen anyone come through it more light-hearted than Howard did.’

Howard Brenton’s Life and Works in Brief

Howard Brenton’s Life and Works in Brief

Early years

Brenton was born in Portsmouth, Hampshire, son of Methodist minister Donald Henry Brenton and his wife Rose Lilian (née Lewis). He was educated at Chichester High School for Boys and read English Literature at St Catharine’s College, Cambridge. In 1964 he was awarded the Chancellor’s Gold Medal for Poetry. [1] While at Cambridge he wrote a play, Ladder of Fools which was performed at the ADC Theatre as a double bill with “Hello-Goodbye Sebastian” by John Grillo in April 1965, and at the Oxford Playhouse in June of that year. It was described by Eric Shorter of The Daily Telegraph as “Actable, gripping, murky and moody: how often can you say that of the average new play tried out in London, let alone of an undergraduate’s work…” [2] Brenton’s one-act play, It’s My Criminal, was performed at the Royal Court Theatre (1966).

Career

In 1968 he joined the Brighton Combination as a writer and actor, and in 1969 joined Portable Theatre (founded by David Hare and Tony Bicat), for whom he wrote Christie in Love, staged in the Royal Court’s Theatre Upstairs (1969) and Fruit (1970). He is also the author of Winter, Daddykins (1966), Revenge for the Royal Court Theatre Upstairs; and the triple-bill Heads, Gum & Goo and The Education of Skinny Spew (1969). These were followed by Wesley (1970); Scott of the Antarctic and A Sky-blue Life (1971); Hitler Dances, How Beautiful with Badges, and an adaptation of Measure for Measure (1972).

In 1973 Brenton and David Hare were jointly commissioned by Richard Eyre to write a ‘big’ play for Nottingham Playhouse. “The result was Brassneck, which offered an exhilaratingly panoramic satire on England from 1945 to the present, depicting the meteoric ups and downs of a self-seeking Midlands family…from singing the Red Flag in 1945 to acting as a conduit for the Oriental drug market in the decadent Seventies.” – Michael Billington (2007). Brassneck was followed a year later by Brenton’s The Churchill Play, again staged by Richard Eyre at the Nottingham Playhouse (1974), another ‘state of the nation play’ about the growing conflict between security and liberty, opening with the image of a dead Winston Churchill rising from his catafalque in Westminster Hall. Brenton’s play “offered an imaginative vision of a future in which basic human freedoms would be curtailed by the state. As so often, a dramatist saw things that others did not’.

Brenton’s next major success was Weapons of Happiness, about a strike in a south London factory, commissioned by the National Theatre for its the new Lyttelton Theatre and the first commissioned play to be performed at its South Bank home. Staged by Hare in July 1976, it won the Evening Standard award for Best Play.

He gained notoriety for his play The Romans in Britain, first staged at the National Theatre in October 1980, which drew parallels between the Roman invasion of Britain in 54BC and the British military presence in Northern Ireland. But the politics of his play were ignored. Instead a display of moral outrage focused on a scene of attempted anal rape of a Druid priest (played by Greg Hicks), caught bathing by a Roman centurion (Peter Sproule). This resulted in a private prosecution by Mary Whitehouse against the play’s director, Michael Bogdanov. But Whitehouse’s prosecution was withdrawn by her own legal team when it became obvious that it would not succeed.

The theme of Brenton’s 1985 political comedy Pravda, a collaboration with David Hare who also directed, was described by Michael Billington in The Guardian 3 May 1985 as “the rapacious absorption of chunks of the British press by a tough South African entrepreneur, Lambert Le Roux….superbly embodied by Anthony Hopkins who utters every sentence with precise Afrikaans over-articulation as if the rest of the world are idiots.” The target of the satire was generally accepted to be the Australian international newspaper proprietor Rupert Murdoch and his News International empire, but the play’s main question mark was about the dangers for society and the state of monopolistic media ownership.

In 2008 most theatre critics expressed surprise that Brenton, long a political firebrand of the hard Left, author with Tariq Ali of several anti-establishment squibs, had written a biographical play about Harold Macmillan, Never So Good at the National Theatre that seemed wholly sympathetic to the former Tory prime minister. It was perhaps forgotten that Brenton, shortly before, had written a challenging play about the biblical figure of Saint Paul and a nimble romance about the love affair between the 12th century theologian Pierre Abelard and his attractive young student Heloise, suggesting a broadening of Brenton’s political outlook if not a Damascene conversion. But it may also be noted that Jeremy Irons’s central performance focused not on Macmillan as a wily political opportunist but on his unruffled urbanity and charm, an old Etonian with a profound sense of decency who eventually loses his way in a world of swiftly shifting values.

- Ladder of Fools, Cambridge University Actors, ADC Theatre, Cambridge (1965)

- Christie in Love, Portable Theatre, Royal Court Theatre Upstairs (1969)

- Gum and Goo, Brighton Combination (1969); RSC at the Open Space Theatre (1971)

- Revenge, Royal Court Theatre Upstairs (1969)

- Heads, University of Bradford Drama Group (1969); Inter-Action at the Ambience-in-Exile Lunch Hour Theatre Club (1970)

- The Education of Skinny Spew, University of Bradford Drama Group (1969); Inter-Action at the Ambience-in-Exile Lunch Hour Theatre Club (1970)

- Fruit (1970)

- Wesley, Bradford Festival (1970)

- Scott of the Antarctic, Bradford Festival (1971)

- Hitler Dances, Traverse Theatre Workshop (1972)

- Measure for Measure (adaptation), Northcott Theatre (1972)

- Magnificence, Royal Court (1973)

- Brassneck, written with David Hare, Nottingham Playhouse (1973)

- The Churchill Play, Nottingham Playhouse (1974); revived by the RSC 1978 and 1988

- The Saliva Milkshake, Soho Poly Lunchtime Theatre (1975)

- Weapons of Happiness, National Theatre, Lyttelton (1976); winner of the Evening Standard award 1976; revived by the Finborough Theatre, 2008

- Epsom Downs, Joint Stock Theatre Company (1977)

- Deeds, written with Trevor Griffiths, Ken Campbell, and David Hare, Nottingham Playhouse (1978)

- Sore Throats, RSC Donmar Warehouse (1978)

- The Life of Galileo, translation from Bertolt Brecht, National Theatre, Olivier (August 1980)

- The Romans in Britain, National Theatre, Olivier (October 1980)

- A Short Sharp Shock, written with Tony Howard, Royal Court at the Theatre Royal Stratford East (1980)

- Thirteenth Night, RSC Donmar Warehouse (1981)

- Danton’s Death, translation from Georg Büchner, National Theatre, Olivier (July 1982)

- Conversations in Exile, adapted from Brecht, Foco Novo (1982)

- The Genius, Royal Court (1983)

- Sleeping Policemen, written with Tunde Ikoli, Foco Novo, Hemel Hempstead then Royal Court (1983)

- Bloody Poetry, Foco Novo, Hampstead Theatre (1984); Royal Court (1987)

- Pravda, written with David Hare, National Theatre, Olivier (1985); winner of the Evening Standard Award 1985

- Greenland, Royal Court (1988)

- H.I.D. (Hess is Dead), RSC, Almeida Theatre (1989)

- Iranian Nights with Tariq Ali, Royal Court (1989)

- Moscow Gold with Tariq Aii, RSC Barbican Theatre (1990)

- Berlin Bertie, Royal Court (1992)

- Faust Parts 1 and 2, translation from Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, RSC Swan Theatre, Stratford-upon-Avon (September 1995); RSC the Pit (September 1996)

- Ugly Rumours, with Tariq Ali, Tricycle Theatre (1998)

- Collateral Damage with Tariq Ali and Andy de la Tour, Tricycle Theatre (1999)

- Snogging Ken with Tariq Ali and Andy de la Tour, Almeida Theatre (2000)

- Kit’s Play, RADA Jerwood Theatre, (2000)

- Paul, National Theatre, Cottesloe (November 2005) [1], Olivier nomination for Best Play

- In Extremis, Shakespeare’s Globe (2006) [2], revived 2007

- Never So Good, National Theatre, Lyttelton (2008) [3]

- Anne Boleyn, Shakespeare’s Globe (2010)

- Danton’s Death, National Theatre, Olivier (2010), a translation from Georg Büchner

- The Ragged Trousered Philanthropists, Liverpool Everyman and Chichester Festival Theatre (2010)

Books

- Diving for Pearls (novel), Nick Hern Books (1989) ISBN 978-1-85459-025-1

- Hot Irons (diaries, essays, journalism), Nick Hern Books (1995) ISBN 1-85459-123-1; reissued in an expanded version, Methuen (1998)

Radio

- Nasser’s Eden (1998)

Libretto

- Playing Away, libretto for Ben Mason’s football opera, Opera North and Munich Biennale (1994); revived Bregenz Festival (2007)

Screenplays

- Lushly (1972)

- The Saliva Milkshake, BBC (1975)

- The Paradise Run, Thames TV (1976)

- Desert of Lies, BBC Play for Today (1984)

- Dead Head, BBC 4-part series (1986)

- Spooks, BBC drama series (2002–2005), fourteen episodes; BAFTA Best Drama Series 2003

- “Traitor’s Gate”

- “The Rose Bed Memoirs”

- “Mean, Dirty, Nasty” (with David Wolstencroft)

- “Nest of Angels”

- “Blood & Money”

- “I Spy Apocalypse”

- “Smoke & Mirrors”

- “Project Friendly Fire”

- “The Sleeper”

- “Who Guards the Guards” (with Rupert Walters)

- “Celebrity”

- “Road Trip”

- “The Russian”

- “Diana”

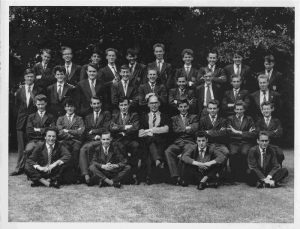

Lower 6th Arts 1960 H Brenton 3rd from Left Mid Row

Lower 6th Arts 1960 H Brenton 3rd from Left Mid Row

Awards

- Evening Standard Award for best play 1976, for Weapons of Happiness

- Evening Standard Award for best play 1985, for Pravda

- Whatsonstage.com Theatregoers’ Choice Award for best new play 2011, for Anne Boleyn

Home Articles News Events Galleries Newsletter Members Forum Links Contact web design by stressfree websites