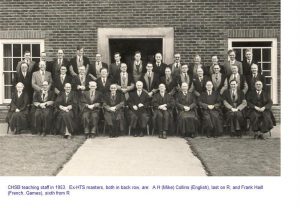

School Staff 1952-1953 with Dr Bishop

School Staff 1952-1953 with Dr Bishop

Masters

All masters at school wore a gown, a tradition which has now disappeared in schools but does, in fact, have value because it contributes to the maintenance of discipline by giving the master a presence which is missing if he teaches in a sweater and jeans and is called by his Christian name instead of being addressed as `Sir’. The gown was also useful because it protected the master’s clothes from chalk dust from blackboards which were an essential item in classrooms of the1940s. Boys stood up and fell silent when a master entered a room and did not sit down until told to do so. The headmaster wore a gown and mortar board when he walked about: he would take off the mortar board while addressing us when he came into a classroom and when he arrived on the platform after all the masters were present at assembly in the mornings. The master and the boys would all rise if the headmaster entered a classroom. The headmaster, who had been appointed in May 1934 when he was 41 years old, was Dr Edgar William Bishop. He gained his doctorate after he came to Chichester. He had experience of elementary school work and held appointments at King’s Norton Secondary School, Birmingham, was senior English and history master at the Judd School, Tonbridge, and was headmaster of the Blue School, Wells, Somerset before coming to Chichester. After he retired he took holy orders and became vicar of a church near Chichester. All the boys and even the masters were somewhat in awe of Dr Bishop. The worst punishment for a most serious offence was to be reported by a master to the headmaster and to be called to the head master’s office for interview.

The senior geography master was Mr Thomas R Holland, MA (Cantab), who had taken both the mathematical tripos and the geographical tripos at Cambridge. He taught us geography from the first year onwards and was also our Form master when I was in Form 2A. He had the nickname Dutchy. He was pernickety: for example, he insisted we copied our homework assignment word for word from the blackboard into our notebooks and would walk around the class to check everybody had done so before anybody could leave. He lived with his family in Chichester in a bungalow about five or six houses along the road from my house in Stockbridge Road. I remember his son, David

Holland who was younger than me: he had ginger hair and was also a pupil at the High School. Later, when I lived in Newbury, I discovered David had studied medicine and was then a GP in practice at Thatcham, close to Newbury. Sadly, he died, leaving his wife Jenny and their children. My wife Jane, who is a chartered physiotherapist and was Superintendent of the Newbury Hospital physiotherapy department before setting up a private practice with three of her colleagues, knew David Holland from her contact with local GPs and knew Jenny Holland who was a health visitor. Jenny has since remarried and is now Jenny Elliott.

The senior history master was Mr Alfred Scales, MA (Oxon). Later he became Deputy Head Master and retired in 1965. Inevitably some boys gave him the nickname Fishy but it was not frequently used. He had read modern history at Oxford. He often told us his Oxford College was the best (it may have been Lincoln, but I am unsure) and was proud of being an Oxford man. He was a popular master who played cricket against the boys in the masters’ eleven and sometimes refereed football games. He maintained good discipline without any difficulty. In the Fifth Form, he started the year by stating we were all going to be successful in the School Certificate history examination provided we followed his instructions and did the work required of us. His method was to dictate two or three model answers to generic examination questions during the course of his lessons during each week. Homework then consisted of memorising these sufficiently to be able to reproduce the content on the following Monday when one of them would be chosen by him in a test which he marked. He explained that these model answers would cover the entire syllabus for the examination and when we took the papers we would be able either to answer any question more or less directly with an essay based on the content of one of the model answers or would be able to put an essay answer together using parts of two of the memorised model answers. In the summer term, he issued his prediction for the questions that would appear in the School Certificate examination paper we were preparing to sit, based on his study of the questions in the previous year’s and earlier papers. Mr Scales’ predictions were remarkably good. The predicted list of questions started with 2-star topics, those he felt certain to come up; 1-star topics, those he thought likely to appear; and no-star topics, those he considered possible questions. He said we should concentrate our revision on the topics in his list rather than on everything we had covered during the year, but those who felt weak in the subject should concentrate first on his 2-star topics, and then on his 1-star topics. If we did as he suggested he said none of us would fail to at least achieve a pass mark in history and more likely would achieve a credit or a distinction mark.

French was taught by Mr Mance, BA. His lessons were efficiently run and he went at a fast pace. The French textbook we used had been written by the school’s 1st headmaster, Mr Herbert F Collins, MA (London), who was recognised as a leading authority on the teaching of modern languages. The first time we saw Mr Mance was when he entered the classroom for our first French lesson. He came in and said `Bonjour mes enfants. Asseyez-vous’, and to the boy who held the door open for the master to arrive he said `Fermez la porte’. He went to the master’s desk and then pointed to a boy at a desk near a window, indicated the window, and said `Ouvrez la fenêtre’. When all this had been done he said we had already understood what he had said in French so we should not find it difficult to learn to write and speak French. Each lesson started with a table of phonetic symbols on the blackboard which we had to chant until he was satisfied he was hearing the correct sounds from us.

The German master was Mr Eric Reeves, BA (Manchester), who also used the phonetic method. He seemed a gentle man but could be stern at times. We were taught German from textbooks using the old gothic script and because German is almost completely phonetic I can still read out loud an unseen German text in gothic script as if I understand every word. I did only one year of German so my comprehension of the language is not great, but it did allow me at university to cope with the compulsory foreign language questions in the final degree paper and to find my way around scientific papers in German later when I was doing research for my PhD in plasma physics.

One of the mathematics masters, Mr M O’Brien, BA, .geni.com/people/Martin-O-Brien was also our Form master for one year. Another popular master, he was known as Mob and appeared in kit during games periods and played for the masters’ cricket eleven.

I think he also taught some physics to first-year boys because there were too few physics masters to replace the senior physics master Mr Gordon Stables, BSc (London) who was called up for war service. When the announcement of the dropping of atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki was made, every- body talked about this amazing development, but almost immediately there was universal curiosity on how such an enormous release of energy was achieved and how an atomic bomb worked. The official publication by the US government, the Smyth Report described the basic physics but it was not easy for the general public to understand. Mr O’Brien had given us a talk at school on how energy is released when a uranium nucleus is fissioned and word of this must have got to parents because it was not long before he was in great demand giving explanatory talks on the atom bomb to clubs and societies over a large area. Mr O’Brien claimed he could see behind him: when he was writing on the board, the board cleaner would come hurtling toward any boy causing a disturbance. Mr O’Brien was responsible for choosing the players for the school soccer teams. In my later years, Edward Brewer was usually captain of the school 2nd XI with Tony Poe captain on some occasions. When Mr O’Brien had chosen the teams, his handwritten notice appeared on the notice board before the weekend fixture with `Captain’ after the name of the nominated person. Once, when this had not been done Ted Brewer mentioned it to Steve Balchin. Someone (probably Steve) pencilled in the word `Captain’ after Ted’s name. Nothing was said about it by Mr O’Brien, but the following week Ted was not chosen as captain. Ted thinks that Mr O’Brien thought that Ted had done it and realises that he should have told him that it was not him and that he did not know who had done it, but masters were treated with considerable deference at that time, which was both a good thing and a problem. Ted recovered the captaincy later.

Another of the mathematics masters was Mr Stephenson. A tall man who had a presence in the classroom that did not invite any liberties or messing about, he was a clear and competent teacher who answered questions without ever making a boy feel foolish.

A new mathematics master, Mr Hulbert, BA, arrived to teach us in the Second Form. We found his passion was Inca history which he would recount in a really interesting way. It arose when he was discussing truncated pyramids.

After a few weeks, when he came to the classroom and asked us to open our textbooks at a particular page, a boy would always say something like `Sir, please tell us about the Inca tortures’. He would reply that we should do some work from the text book and if there were time he would finish the lesson with some more Inca history. Word of what he was doing must have reached the headmaster because Mr Hulbert disappeared at the end of the school year and was replaced by a master who concentrated on the mathematics.

A master who was visually outstanding was Mr Geoffrey W Marwood, BA. He was a prominent member of the Chichester Amateur Dramatic Society and was rather flamboyant: uniquely among the masters, he wore a white coat and royal blue trousers. He taught mathematics, but I recall that he took classes with us for other subjects on several occasions when our usual subject master was absent. On one occasion when Mr Marwood was looking at Edward Brewer’s solution for a geometry problem he said `I would call that a proof by attrition’. Mr Marwood was interested in local ancient history and published a booklet The Stone Coffins of Bosham Church. He also wrote the church guide The Story of Holy Trinity Church Bosham which he revised in 1995. The local tradition is that Godwin, the father of King Harold, was buried in Bosham. The coffin was opened in 1954 and in Marwood’s booklet, he notes that it was found to contain the bones of a man aged over 60 years with traces of arthritis. A dispute arose recently whether the burial place of King Harold was at Waltham Abbey or at Bosham, leading to permission being sought to reopen the Bosham coffin for DNA testing. Those involved appeared to be unaware of Marwood’s booklet. It is known that Harold died aged about 44 years so the Bosham coffin cannot be his. The petition to open the grave in the church was dismissed by the Consistory Court of the Diocese of Chichester on 10 December, 2003.

The master who taught us music was Mr Thomas Buxton who also taught German. Before reaching the Fifth Form we had one period of music a week. The lesson was essentially a singing lesson in the assembly hall with the master playing the piano. We learnt nothing about music and I learnt nothing about singing. For most songs I could not sing the range of notes without changing to a lower or higher octave during the song, so for the lesson, I migrated to the back row where some of us spent the time playing a game on paper called battleships. Each of us drew a grid of squares and marked two battleships (four squares long) and two destroyers (three squares long) at random on the grid without the others seeing; we then whispered grid coordinates to each other with the aim of hitting either a battleship or destroyer, the winner being the first to sink all the other’s battleships and destroyers.

The physical education master, or gym master as we called him, was Mr Ashton. He replaced a master known as Killer Colgan who had already joined the services before I went to the school and had not returned by the time I left.

His reputation was still talked about by the boys who had known him. Mr Ashton had trained at the Carnegie Institution in Canada and wore tracksuits and sweaters with the Carnegie name and emblem on the back and front. He did not have a degree and on speech days when all masters wore hoods with their gowns he, with Mr Watson who was the art master and deputy head and had trained at art school but also did not have a degree, wore only a gown. Mr Ashton once made the mistake of appearing dressed in his track suit outside the building containing the gymnasium and the changing rooms for PE and games. He received a written reprimand from the headmaster in which Dr Bishop said he expected his masters to be properly dressed at all times in the main body of the school, noting it would be unacceptable if when he was walking around the school with parents they encountered a master who was not properly attired.

Mr A H Watson, the deputy head and art master, was always mentioned every year in the Christmas carol singing. His Christian names were Arthur Harold and we always sang `Arthur Harold angels sing, Glory to the newborn king.’ We also amended the words `While shepherds watched their flocks by night to `While shepherds washed their socks by night’. Mr Watson was known as Monkey: I did not know how the nickname originated, but Geoffrey Wills (1943-1952) told me that it came from a product called Watson’s `Monkey Brand’. Mr Watson was a small, slightly built man. As deputy head, he oversaw the Prefects’ Court, to which boys were summoned for disciplinary offences. If the court recommended caning for a serious offence it could only be carried out by Mr Watson. He wore glasses but took them off to see things close up and claimed to have the ability to see great detail: this puzzled us but he told us he had microscopic vision and could see everything that went on in class. We did not then know about the physiology of the eye. In fact, his vision defect was that he could only focus at a short distance from his eyes and needed his glasses for all normal vision. Later in life, he was proud that for reading he did not need to use his glasses. He had a phrase he used often in art classes: when a boy doing a drawing asked him if he thought some part or all of it had been drawn correctly he would reply `If it looks right it is right’.

Mr Charles (Percy) Pelham taught us English and was also the school librarian. He seemed somewhat unapproachable, but it was probably due more to an inherent shyness than a forbidding manner and a seeming lack of a sense of humour. He was away sick for a long time with a problem with his leg and when he returned following an amputation he walked with a stick. Mr Pelham would criticise sharply any use of poor English and be particularly scathing of any boy who used the word `nice’ in an essay except in its proper sense. In the First Form, we were not initially allowed to use the library. When the time came Mr Pelham took the whole class to the library in place of the normal English lesson. We were told about the value of books, told never to deface a book by writing anything on the pages, never to turn a corner down to mark a page, never to break the spine of a book by opening it beyond an angle of just under 180°, and never to read a book with dirty hands or when eating or drinking. He explained the library catalogue which used the Dewey decimal system. Finally he demonstrated the method of taking a book from a library shelf: the forefinger should be placed along the top of the book taking care not to damage the binding at the top edge of the spine, the finger should then be used to tilt the book backwards toward oneself and the thumb and second finger used to grasp the top of the book which could then be pulled out from the line of books. He gave Edward Brewer a hard time. Ted was in hospital when his first term in Form 1A started so was two weeks late in arriving. Mr Pelham did not like his Sussex accent which he thought was common and humiliated Ted in English classes by making him stand up to say things like `Oi must troi to say oi roightly’. On one occasion when the class was doing clause analysis, Ted had set out a table in columns with the headings noun, adjective, verb, etc. written in capitals. Mr Pelham looked at his book, pointed at the headings and said `In this school, we don’t print, we write.’ Ted thought he was a snob. He discovered that Mr Pelham had a car completely out of character; it was a Morgan three-wheeler with two wheels and an exposed engine at the front and one wheel at the rear. He never came to school in it. Ted remarked to me recently that when petrol was available again after the war Mr Watson proved to have the best car; it was a grey and blue Wolseley 12/48 series 22.

Ted has told me of another much younger English master that I do not recall. He was Mr Lucas. The boys gathered that Mr Lucas was worried about being called up for military service which certainly would not have suited him as he was a rather shy person. He acquired the nickname Gnome. Ted cannot recall what happened to him. However, he had fallen for the headmaster’s attractive daughter, Miss Bishop. This encouraged Poultney, a boy in our Form, to write a version of the popular American wartime song “This is the Army, Mr Jones” from Irving Berlin’s all-soldier musical of 1942 “This is the Army” which had verses

This is the army, Mr Jones.

No private rooms or telephones.

You had your breakfast in bed before

But you won’t have it there anymore.

This is the army, Mr Brown.

You and your baby went to town.

She had you worried

But this is war and she won’t worry you any more.

Two of Poultney’s verses were:

This is the army, Mr Lucas,

You cannot mark your English book as.

We had you worried

But this is war and we won’t worry you any more.

This is the army Mr Gnome,

You cannot take Miss Bishop home.

She had you worried

But this is war and she won’t worry you any more.

Edward Brewer, Edward Folkard and Donald Weddell when out for a bicycle ride one Saturday morning saw Mr Lucas and Miss Bishop on a country road north of Chichester engaged in the same activity. His bicycle, like most teachers at the time, was equipped with a large basket on the handle bars. Politely, the two Teds and Donald did not let Miss Bishop and Mr Lucas see them, which was a kindly act for schoolboys, but people were nicer in those days.

Handicraft was taught by Mr Samuel Lambert. We always called it wood-work. The handicraft room was the large wooden building on the right near the main entry gate. We were trained in basic woodworking skills and the construction of furniture and made small items in wood and practice pieces of complicated joints. Mr Lambert kept a close eye on us when we used woodworking tools and frequently said to boys as he patrolled between the benches `Keep your left hand behind the cutting edge’. At the end of the lesson, nobody could leave until every tool was accounted for and replaced in its storage rack and all wood shavings and sawdust had been cleaned up and placed in waste bins. Mr Lambert was making himself a cabinet for his HiFi equipment: it seemed to near completion slowly and we never saw him working on it. It already contained his HiFi equipment. He was keen on classical music and persuaded us to attend his Music Appreciation Society after school. One boy who was not keen on classical music asked if we could listen to some of the big bands popular at the time and argued that a trumpeter like Harry James was better than the trumpeters in classical orchestras because he was not only the bandleader but also played solos. I suppose that this was true of outstanding clarinet players like Benny Goodman and Artie Shaw. After that Mr Lambert used to include a big band recording in his programme, but always tried to get us to appreciate classical music. Edward Brewer recalls that he played us the Scherzo from Henri Litoff’s Concerto Symphonique No 4 Opus 102 as an example of rhythm in classical music. Handicraft was not just learning a skill, but was taken as a school certificate subject in the Fifth Form. The syllabus included not only learning to work properly with wood to prescribed dimensions and with complex joints, but also knowledge of the basic properties of different woods, the history and design of wooden furniture and the ability to recognise the work of famous designers such as Hepplewhite.

We were taught chemistry by Mr Pasquill. Our notebooks in the First Form into which we copied notes from the blackboard were somewhat monotonous because every section was headed The Preparation and Properties of followed by the name of whatever substance such as oxygen or nitrogen we were being told about. Some were odourless and colourless, but others had horrible smells.

One boy discovered a trick with lighted Bunsen burners he could play when we had a laboratory class. With the gas turned off where he was sitting, he would remove the Bunsen burner from its rubber tube, leaving the tube connected to the gas tap at the other end. He would then put the end of the tube in his mouth and switch on the gas tap at the same time as he blew as hard as he could into the tube. This was sufficient to overcome the low pressure of the laboratory gas supply and put a puff of air in the supply tube to the other Bunsen burners along the bench causing them be extinguished when the air arrived, thus generating a rush from the other boys to turn off their gas taps.

Mr Pasquill enjoyed a demonstration he gave to all first years. He would ask a boy to stand next to him behind the raised bench at the front so that we could all see and ask the boy to copy what he was going to do. Mr Pasquill had a beaker of colourless liquid standing on the bench: he put his finger into it and then put a finger into his mouth. The boy did the same, but quickly took his finger from his mouth with an expression of disgust. Mr Pasquill then said that the boy had not copied what he had done: Mr Pasquill had put his second finger into the liquid but had put his forefinger into his mouth, while the boy had used the same finger for both actions. He said he had done it to make us remember the importance of close observation of what we were required to do when repeating an experiment he had demonstrated to us.

Mr Gahan taught classics. He had a reputation for being sarcastic to boys in class. I did no Latin, but decided to go to his after school class in Greek. It was interesting at first to learn the Greek alphabet, but I thought the texts were rather boring and did not continue with the classes.

Mr Pring was a new master who arrived and taught us German for some lessons. He spoke English with an accent I was unable to place, but which some boys thought was German. As a result, he was thought by some to be a German spy and was treated by them behind his back to the Hitler salute and a muttered Sieg Heil. He left after two years. Saying the phrase Sieg Heil in Germany today is a criminal offence punishable by up to three years imprisonment unless the usage is for teaching, art or science purposes when it is exempt.

Another new master whose name I think was Mr Evans was a big, bulky Welshman, called Tony Pandy by the boys. He taught physics and became renowned when a boy in his class in the physics laboratory was persistently disruptive. Mr Evans called him to the front and to our astonishment grabbed the front of his coat, lifted him off his feet and then deposited him outside the door in the corridor, telling him to stay there until he was told to return. We all reckoned that Mr Evans was a very strong man. It was not uncommon for boys to be expelled from the class to wait outside for a short period, but it had the risk feared by the boy that he would be discovered there by the Headmaster on one of his occasional tours around the school and be required to explain himself. Mr Evans had no further problems with discipline. Edward Brewer still remembers him shouting “Breewah, what you doin’ boy?” in his strong Welsh accent.

We had a careers master although I do not remember who it was who undertook the task. It appeared that we all had the same brief interview which took the form of being asked `Navy, Army or Air Force?’ I replied `Fleet Air Arm’ which did not go down too well because he had only three lists.

There were other masters whose names I recall:

Mr Eric Smedley, BA (Manchester)

Mr Oscar Lloyd

Mr Norman Siviter

Mr Haill

Mr Collins

I had no lessons from any of these masters and so cannot say anything about them.

Mistresses

Towards the end of the war it was increasingly difficult for Dr Bishop to find male teachers to replace those who retired or left, and for the first time in the history of the school one or two female teachers appeared. The first was

Mrs Holland, BA, the wife of the geography master, a middle-aged lady with experience of teaching who stood no nonsense from the schoolboys and fitted in with no problems. She came to take over when her husband contracted tuberculosis and was on sick leave for a long time before he returned. We were uncertain what to call her, and during our first lesson with her, the obligatory use of `Sir’ to address a master was changed to `Please Miss’ by the first boy to address her. She immediately told us the use of `Miss’ was not permitted and we should address her as `Mrs Holland’ or as `Ma’am’. At that time it was not considered proper for male and female teachers to share the same staff room so a classroom was allocated for use as a staff room by Mrs Holland and subsequently by other women teachers.

The second woman teacher who came did not stay long. Her name was Miss Webber. She was younger than Mrs Holland and was not married. She taught French. Some of the oldest senior boys (who would have been about 18 years old, having taken the longest and least academic path through the school) who were accustomed to go to public houses, saw her one evening with a group of men at a table playing a game called Bottle. To this day I do not know what the game comprises. Thereafter she had the nickname Bottle at school. She was reputed to associate with American GIs. We heard that Dr Bishop was not too pleased with her reputation and shortly afterwards she left. Miss Houghton joined the staff for a period, but I do not remember much about her.

One of the most notable arrivals was the head master’s daughter, Miss Bishop, BSc. She had just completed her degree in biology and her post-graduate teaching diploma and was in her early twenties. She took over biology teaching. She was a very attractive young woman and all the senior boys fell in love with her. One boy was so enamoured of her he would slip out of assembly in the morning as the staff were still sitting on the stage and would run all around the corridor outside the main hall so he could walk past Miss Bishop as she returned to the women’s staff room. Another over-developed boy (I think he was called Pitt) who fancied himself with girls had the audacity to ask her to go out with him, but she could adopt her father’s intimidatory presence and he received a suitable cold and scornful response and rebuke. School boys being what they are, I have to mention that in one of the classrooms that had a table and chair instead of a desk for the teacher many boys managed to drop their pencil on the floor and would get down on hands and knees in the aisle to recover it so that they could look at Miss Bishop’s legs under the table.

Miss Gertrude Lewis, who was the school secretary before the war, moved from her post to join the teaching staff when it was depleted by masters leaving for war service. She was older than the other women teachers and was short and petite. Her subject was English and initially, she replaced Mr Pelham when he was on sick leave for surgery to his leg. She was very competent and remained on the staff after Mr Pelham returned.